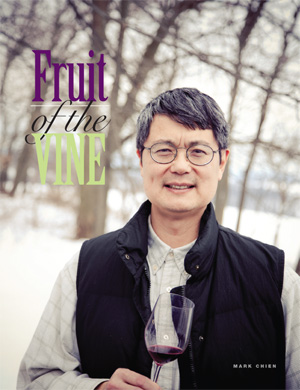

Mark Chien Helps Pennsylvania’s Wine Industry Take Root and Ripen

by Krista Weidner

When you think of fine wine, you might think of France, Italy, or Napa Valley. Chances are Pennsylvania doesn’t come readily to mind. Historically, our Commonwealth hasn’t been known as a wine region, but that’s starting to change thanks in part to the work of viticulturist and extension educator Mark Chien.

When you think of fine wine, you might think of France, Italy, or Napa Valley. Chances are Pennsylvania doesn’t come readily to mind. Historically, our Commonwealth hasn’t been known as a wine region, but that’s starting to change thanks in part to the work of viticulturist and extension educator Mark Chien.

“Wine has been around for a long time,” says Chien, who is based in Lancaster County. “What we think of as wine started in the central Eurasian area about two thousand years ago. You experience that tradition in a great glass of wine, but how do you bridge that chasm between grape and glass? I think the ancient wine growers faced the same challenges we do today. A grape grower who hopes to make quality wine has a lot to learn. That’s where extension comes in.”

Today, in Pennsylvania more than 130 bonded wineries produce about a million gallons of wine each year, with help from independent commercial vineyards that supply their grapes. Interest in growing grapes and making wine is on the rise, with more than 60 new wineries in Pennsylvania in the last 10 years.

Part of Chien’s role is to educate new and potential growers about what they’re getting into. “The way it usually happens,” he says, “is that somebody comes to me who is very successful in another career—a doctor, lawyer, entrepreneur, every career imaginable other than one having to do with agriculture. If I’m lucky, they’ve at least had a backyard garden. So how do you give that person who’s about to embark on an agricultural endeavor that can cost up to $30,000 an acre just to install even the most remote chance of succeeding?

“I explain to them that grapevines are amazing plants—very tough, very hardy. Once they’re in the ground they are hard to kill. Anyone can grow a grapevine. But if you want to grow a grapevine with the potential to produce really high-quality wine, then you need to transform yourself into a person who really understands this plant and how toWeidnernurture it to produce fine wine grapes. The wine grape is an extremely demanding crop that responds to nuance and subtlety in ways you could never imagine a plant could. And you have to educate yourself to understand that. Nine out of 10 people in this industry are self-taught, and many have been successful beyond my imagination.” In his work with wine grapes, Chien collaborates with other Penn State faculty in horticulture, plant pathology,entomology, and crop and soil sciences. “We have quite a large network of people helping with grapes, even though for many of them it is not part of their formal work assignment,” he says. “Rob Crassweller in horticulture manages the new USDA wine grape variety trials at Penn State’s Fruit Research and Extension Center and Northeast Grape Research Station. Elwin Stewart did outstanding work on trunk diseases that cause vine decline. Jim Travis and his grape pathology team did cutting-edge work on using compost in vineyards and organic viticulture practices and provide outstanding disease-prevention extension services to the industry.”

Three major types of grapes are used to make wine. Vinifera refers to classic European grapes most people are familiar with, such as Merlot, Cabernet Franc, Pinot Noir, Chardonnay, and Riesling. Hybrid grape varieties, including Vidal, Seyval, Chambourcin, and others, are well adapted to Pennsylvania’s growing conditions and are very popular. The third type includes Native American varieties, such as Concord, grown mostly for juice but also used for wine.

Pennsylvania presents unique challenges for all varieties. Differences in climate—from the warm, wet weather south of the Appalachians to our own “frozen north”—present hurdles. Topography is another challenge. Diverse soils range from slate and shale along the hills to silt loams in the Chester-southern Lancaster region to sandy-clay soils near Lake Erie. “The grape varieties we need exist here,” Chien says. “We just need to match those varieties to the right places. I’m convinced, for example, that Bordeaux varieties would do well in Adams and York Counties, and the areas with gentle south slopes, well-drained soils, and warmer climates would be very accommodating to vinifera and hybrid varieties.”

The significant challenges presented by Pennsylvania’s soil conditions and weather, which include winter injury, diseases, and pests, demand a certain degree of determination on the part of growers. “We have particular challenges in this region that sunny, arid regions do not have,” Chien says. “That just means we have to be much better growers to make fine wines.

“In Napa Valley, if a consumer encounters a bad bottle of wine, he can just go to the next winery in the next driveway with the full expectation that this one will be better. But someone who tastes a bad Pennsylvania wine will probably write off all Pennsylvania wines. We have so many newcomers to the industry and such a high risk factor for producing a bad product. As in any emerging wine region, we’re presented with the challenge of digging ourselves out of the quality-perception hole. The goal in all of my work with growers is to build a healthy, sustainable wine industry that has markets where Pennsylvania wines can be appreciated by consumers and critics alike.”

In his work with both new and established growers, Chien focuses on short-term, mid-range, and long-term goals. In the short term, he helps growers implement practices needed for a successful growing season. “Everything that affects grape quality—disease, pests (like insects), weeds, and birds—can be controlled to some extent,” he says. “We can’t control the weather and larger systems like soils, at least while vines are actively growing. But we can optimize cultural practices and disease and pest control, and if the weather cooperates somewhat, we have the potential to make world-class wines.”

At the mid-range, Chien helps growers choose the best sites for growing wine grapes. Well-drained soil creates a better-balanced vine. Planting vines in an area that’s not frost prone helps vines retain their leaves and can extend the growing season, which is especially important for late red varieties. Finding an area in a rain shadow that consistently has minimal precipitation will result in less disease and a better chance of growing high-quality grapes.

The long-term goal in growing wine grapes, Chien explains, is to coax those grapes to the correct physiological ripeness that results in the potential for world-class wine and to build viticulture and winemaking into a healthy, sustainable industry in Pennsylvania.

Vineyards and wineries are good for Pennsylvania in several ways, Chien points out. First, they help rural areas by protecting valuable historic farmland. Grapes are one of the few crops to offer enough financial return to fend off developers. Every vineyard and winery in Pennsylvania is family owned and operated, helping protect the tradition of small family farms in the Commonwealth. Vineyards and wineries also help provide stable jobs and tax inputs into rural economies. In the tradition of Napa and the Finger Lakes, they are a boon for tourism. There are eight successful wine trails in Pennsylvania, attracting “city folk looking for a country experience that only the view and taste at a winery can deliver.”Chien is encouraged by what he calls the “new generation” of wine growers entering the industry. “These are now-grown kids whose parents own vineyards. They went to college and got the Wall Street or Hollywood job and decided to come back to the farm to work with their parents. Tom Carroll [see sidebar on p. 25], for example, set aside a successful Hollywood acting career to grow wine on a historic farm in Bucks County with his parents. It’s a delightful and rewarding side of the industry.”

In his 10 years as an extension educator, Chien has come to discover the loyalty of Pennsylvania growers to their location. “Many of the potential or new growers who come to me are in the demographic category that they could just as easily buy a vineyard in California—wherever they want—where it’s Easy Street viticulturally because the sun shines all the time. Why do they want to do it here? One could argue that Pennsylvania’s one of the hardest places in the world to grow grapes for high-quality wine. But what I’ve discovered is the importance of place. People who live in Pennsylvania want to stay in Pennsylvania. If they have a passion for wine and they want to grow grapes and start a winery, I don’t believe for a second most of them would consider going anywhere else to do it. Maybe they have their family farm, they’re not leaving, and they’re seizing the opportunity to do something different.

Download the Article Here

An article about Mark Chien that appeared in FLY magazine.

Tom Carroll Jr. remembers when he met Mark Chien in 2000. “Mark said, ‘They hired me at Penn State. I have a background of growing grapes for more than a decade. I’m here to help you, and it won’t cost you anything.’ That did it for me. I hadn’t realized you could grow good wine in Pennsylvania. He likes to say that the best and worst thing about our region is that our soils can grow just about anything. Just because you can keep a vine alive doesn’t mean it will result in good wine. I learned from Mark that quality starts and ends in the vineyard.” Through annual site visits from Chien and by attending workshops, Tom learned on the job. “I went to every workshop for over two years,” he says. “We wouldn’t have been able to do it without those workshops. They gave me the tools and knowledge I needed in an environment where I could meet other growers and learn from their experiences and make my own decisions.”

Jan Waltz (’89 Animal Production) and Kim Waltz grow 16 acres of wine grapes and operate a successful winery on their fifth-generation family farm. Mark Chien helped them improve their already established vineyard. “He did a site assessment and made recommendations, and we also benefited from his workshops,” says Jan, who is a college alum. “Mark’s strength is bringing growers together so that both new and existing growers can learn about successful practices. He has helped us grow grapes better, and that transfers into better wine quality. Without a doubt there are some really good wines made here in Pennsylvania, and Mark has played a big role in bringing that about. It’s been interesting to see the wine industry take root and begin to develop into a well-respected industry throughout the world. We’re moving toward that goal, and extension is helping us grow world-class wines.”

Brad and Christy Knapp have been growing wine grapes since 1995. Brad emphasizes the importance of terroir in grape growing and winemaking: “Terroir is a French term that refers to a sense of place and all of the components of a growing site: soil, water, sunlight, climate, varieties, management, plant materials, viticulture, and winemaking. A wine that expresses terroir is typical of the region, and if you taste enough wines from a region you’ll start to detect similarities in them. For example, our area has a lot of slate in the soil and a cool climate, and our wines reflect those qualities.”

For the Knapps, Mark Chien’s guidance and expertise have been invaluable. “The grape-growing community is small,” Brad says, “and it’s hard to get information about varieties and what works and what doesn’t. We started out with minimal knowledge and we’ve learned a lot through talking to Mark and attending his seminars, as well as talking with other growers and just plain experience.”